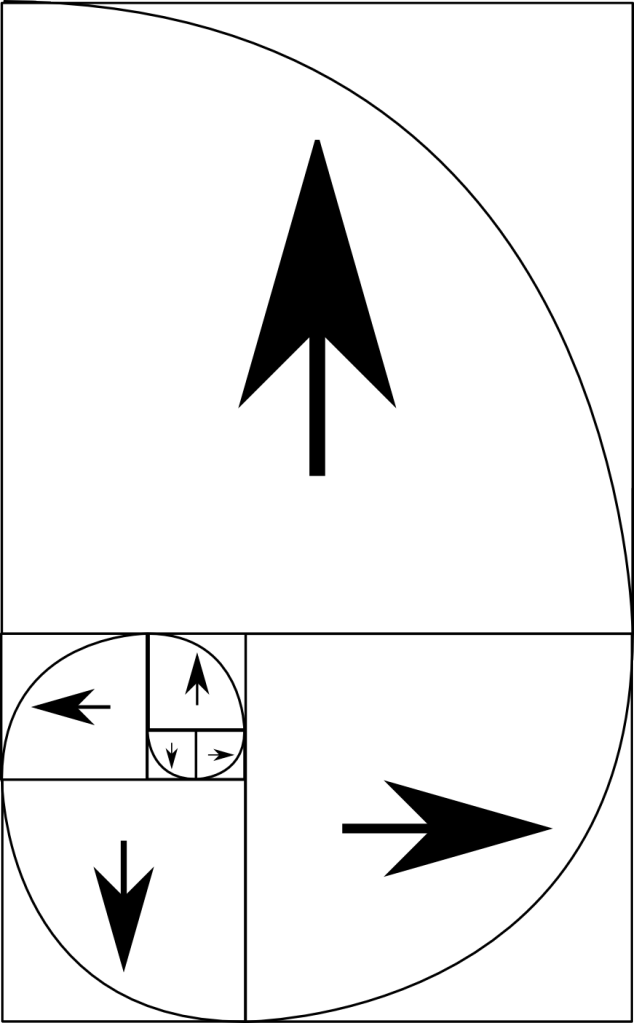

This is the blanket I'm working on, with the eventual goal of having it be a bed-sized spiral.

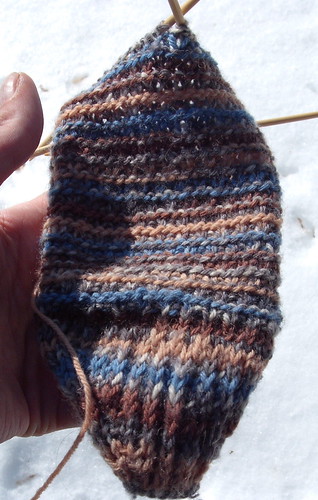

Twirling twist socks - One foot

This is how far I've got in knitting the socks that woke me up. I'm just about ready to start knitting the heel flap. After that, the cable that features prominently on the foot here will split into two branches, each of which will twirl in opposite directions.

The cables will continue twisting in the same way as the cable on the foot, but will gradually make their way to the back of the sock, cross each other, then come back to the front of the sock again.

And again, the nice thing about this design is that, when it comes time to write down the pattern (which I seem to do after one sock, then follow it for the second) it's actually relatively easy to explain. Or, rather, it'll be easy to write down the exact stitches to make to end up with the same result.

Woken by socks

Dear knitblog,

I know I've been bad at updating you. I didn't knit from March through October. But I've started again. Working on a blanket now. All placid and black hole. And what I would like to cite as a sign of obsessive attachment:

I was woken up tonight by a pair of socks.

Not just any socks, but a sock pattern pretty enough that I can use my Knitpicks pretty-pretty-pet-it-pretty yarn on. (An xmas gift)

Socks where cables spiral around each other in a manner that is wholly an illusion, and is easy to knit. A pattern that I think I'll be able to actually chart and put up, unlike some of the more, shall we say, esoteric1 patterns I did in February and March.

The idea is this: A line of c2x2 twist up the foot, splitting into two cables that twist around the ankle, in opposite directions, propelled by KFBs and p2togs.

Anyway, I'm casting on a toe, and I'll see where it takes me!

- By which I mean 'needlessly complicated'.

Sierpinski/Koch Scarf - Halfway there

Mutations

A few days ago, I was approached by colorlessblue. She had a pretty sock pattern made up of triangles, but it required her to use exactly 64 stitches around.

Her difficulty was that she couldn't find a gauge in which that worked. Me first reaction was to say, "well, that's not a big deal, the pattern is trivial to make fit on a multiple of 12 or 14 stitches." Then I tried to explain what stitches to remove, and it really quickly became messy.

So I stopped for 15 minutes or so and drew a few patterns. As I started, she clarified that she didn't want to purl.

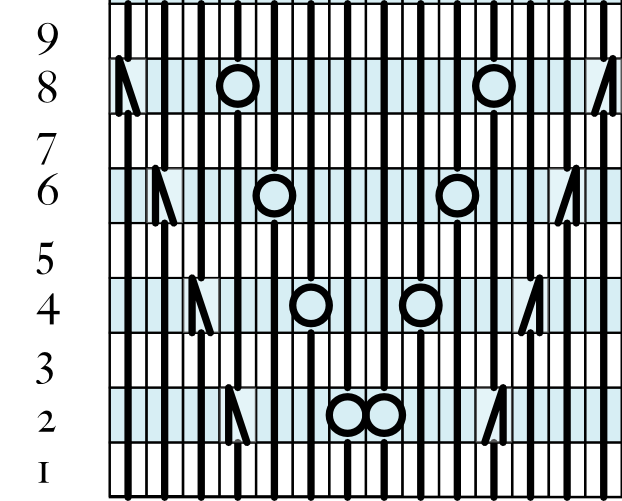

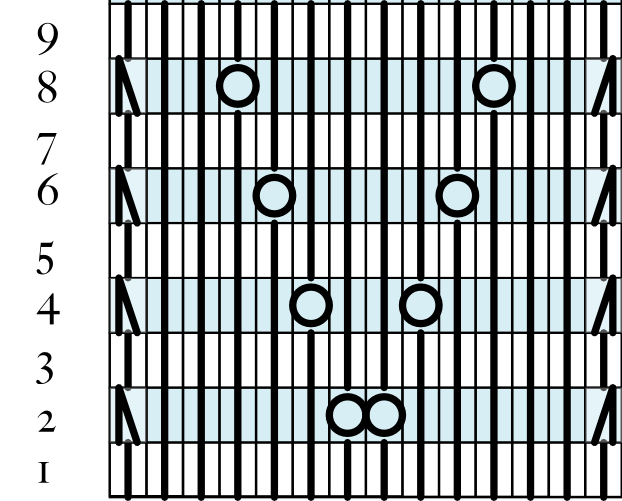

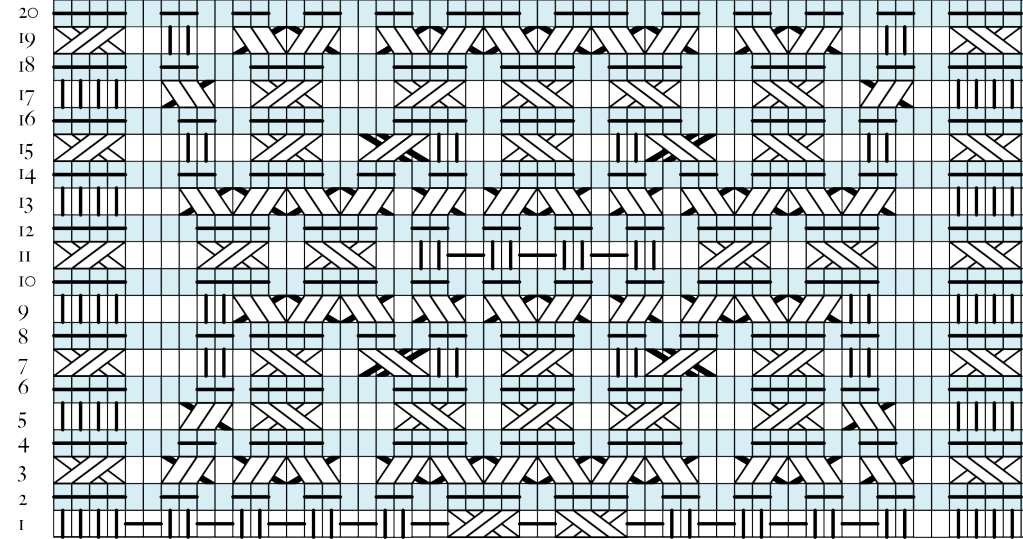

However, the absence of purl stitches meant that the resulting pattern would be triangles of vertical knit stitches with a zigzag border of slanted stitches. So, my next thought was, "Why not make the slanted stitches into the motif. That resulted in this pattern:

It's not perfect by any means. The k2tog and SSK being next to each other results in a ladder. Were I continuing that tangent, I'd turn all paired decreases into double decreases. Also, as it turns out, I didn't like how the paired yarn overs at the apex of the triangle looked.

At the same time as I was thinking that, I also wondered what would happen if the triangles were offset by half a repeat, giving the whole pattern a longer period before it repeats.

It's not perfect by any means. The k2tog and SSK being next to each other results in a ladder. Were I continuing that tangent, I'd turn all paired decreases into double decreases. Also, as it turns out, I didn't like how the paired yarn overs at the apex of the triangle looked.

At the same time as I was thinking that, I also wondered what would happen if the triangles were offset by half a repeat, giving the whole pattern a longer period before it repeats.

This pattern (which is almost the same as a Barbara Walker one) has the property that the knit stitches actually form themselves into vein-like curves: the diamonds end up looking like oval leaves.

I tried knitting it half in knit and half in purl, to see if that would give the leaves more shape, but that ended up being a step too far: The lace lost enough of its definition that the pattern looked awkward and no longer anything like leaves.

I think I'm likely to use this one at some point, possibly as a motif one some leaf-patterned socks that I keep not getting around to. Before I do, I'm likely to put it through one more mutation, reducing it to about half the size and extending the widest part of the leaf by two rows, so that it more accurately matches the shape of a beech leaf.

Most of my charts seem to follow a similar pattern of starting point and progressive mutation, followed by a test knit, correction of discovered problems, a further test knit and possibly correcting steps that went too far.

It's like saying "just one more row", but "just one more change" instead.

Braid-pattern pullover -- Prelude

I'd be the first to admit that I think of myself as a sock-and-hat knitter. I like my projects the way I... Never mind, I'm not going to finish that chestnut. Suffice it to say that I like my projects small enough that I can always keep the end in sight.

That said, I picked up two bales of wool this week; bulky natural wool in a pleasant brown. Along with that, I expanded what is apparently becoming an Addi collection. Essentially, I've committed to knitting a sweater.

As is my wont, I started by browsing the internet to determine what kind of sweater I wanted, then searching Ravelry for patterns. As usually happens, I got frustrated. Fortunately, Elizabeth Zimmerman has a pattern, described in proportions, for a warm baggy pullover. Less-fortunately, it's steeked. After more research and not a little bit of swearing, I decided to blissfully close my eyes and pay no mind to those instructions. After all, I have many many many stitches between me and slicing two holes into my knitting.

Plenty of time to chicken out and re-think the pattern as two trapezoids sewn together with the arms attached by picking up off the selvedge. Plenty of time to consider that sewing two trapezoids together will be far less solid than biting the bullet and knitting the whole thing as a tapered cylinder.

Plenty of time to knit swatches.

This is what I'm using as a swatch. This pattern, repeated over and over, is intended to make up two front panels of the sweater. The intent is to swatch it to see if it looks right and also to test texture and gauge of the wool and needles. As I'm more than mildly worried that 5mm needles (my preferred size for worsted) will simply be too tiny for bulky.

After only a little bit of discussion and plotting, I realised that the back of the sweater really deserves a different pattern from the front.

Rather than two panels of four-strand braids, the back has a single panel, centred, that makes a twelve-strand braid or knot. Fortunately, this pattern will look pleasing so long as the front panel does, so I only need to knit the one swatch as a test pattern.

In keeping with my three-project rule, I'm not to start a pair of socks or a hat or anything else until I've finished with this swatch. Further, once I've committed to the sweater, that's one of the three available slots for patterns taken up. So, likely, I'll knit the swatch, knit some socks (I have a pattern that I want to try), possibly knit some more socks (I actually have two patterns waiting for me), maybe finish a hat, and then get to the sweater, just in time for it to be too warm out for sweaters.

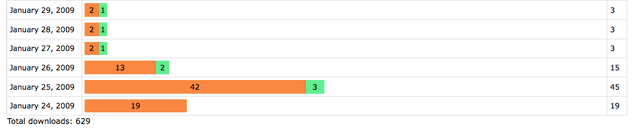

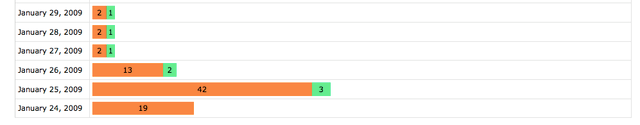

Ravelry Hack #1 - Counting downloads

So, I like Ravelry's designer pages. They're great for indulging my vanity. I tend to check my downloads every once in a while, just out of curiosity, to see if anyone's downloading my patterns.

But one thing it's lacking, and that I'm generally curious about, is how many times they've been downloaded in total. The page doesn't indulge that curiosity. I initially considered putting in a feature request, but then got sidetracked by geekery.

See, the Ravelry downloads page is remarkably readable HTML. Which led me to a quick and easy conclusion: I can fix this in Greasemonkey.

Even having forgotten most of what I learned about the Javascript HTML DOM last time I wrote a Greasemonkey script, it took just over two hours.

With added daily counts on the right-hand column and a "Total Downloads" field at the bottom of the graph.

Installation

If you are using Firefox without Greasemonkey, a compiled Firefox addon is available here. Download it, unzip it and drag it into your Firefox window. It should ask to install, like a normal add-on.

If you have Greasemonkey installed or are using Opera, download the Greasemonkey script file and install the user.js file by:

Firefox: by dragging the file into your Firefox window. Greasemonkey should open, displaying the affected URL and ask you if you wish to install.

Opera: The path where User Javascript files are loaded from is indicated in Preferences/Advanced/Content/Javascript Options. If no path is indicated, choose one. Place the user.js file into that directory.

Knitting is an acceptable Lisp

So, I'm a knitter. And I pretend to be a designer some days, when I'm not knitting endless swathes of k2, p2 rib. But first and foremost, I'm an unabashed geek.

As such, I took a look at KnitML. And it's neat. Well, in theory, it's neat. In practice, I haven't got the java dependencies set up on my computer yet to play with it. I do intend to do that, and am downloading them, but while I wait for them, I want to ponder through an idea that's been percolating in my brain.

Namely, I think of knitting patterns in two ways. One is the chart. This is how I write patterns, really. And given the choice between a chart and a list of stitches, I'll pick the chart every time.

It's a question of information density. The chart presents all the information that I need, in the least amount of space while still being human-readable.

It's a fairly simple pattern, embedded moss stitch rib. And can be easily transformed into a written pattern:

- p2, k2, p1, k1, repeat to end of round

- p2, k2, p1, k1, repeat to end of round

- p2, k1, p1, k2, repeat to end of round

- p2, k1, p1, k2, repeat to end of round

This is where my brain starts making clicky noises. See, my immediate reaction to that is that it's a simple program. One that generates a handsome little ribbing.

However, my second line of thought runs straight for a programming principle: Don't Repeat Yourself. My process for generating a pattern is to draw charts in Inkscape, test those charts by knitting them, then translate the chart into written instructions. In future, I may also want to make my charts available in KnitML.

What this immediately says to me as a programmer is that I should have a single piece of data from which I can generate:

- PNG graphics

This is the format I use to show charts. It's a useful format in that it does a good job of reducing low-colour line drawings (like knitting charts) to a fairly small file size with no loss of detail or crispness.

This is an even worse format to use as a data source, though. Rather than just interpreting the XML that SVG gives, I'd have to start into OCR territory. - SVG graphics

This is the format that I actually use to make charts. Unfortunately, it would be a considerable effort to use it as a starting point: Anything more complicated than a knit or purl stitch are relatively complex "groups", rather than simple objects.

However, they work admirably as a way to draw charts, and from my perusal of the spec, should be able to be drawn programmatically fairly easily. - HTML lists

This actually isn't a bad starting point. Not good enough that I'd want to use it as a data source, but not bad enough, either, to discard it out of hand.

Specifically, if I look at the HTML describing the pattern:<ol>

Other than the <ol> and <li> tags, this actually isn't a bad representation of the data at all.

<li> p2, k2, p1, k1, repeat to end of round

<li> p2, k2, p1, k1, repeat to end of round

<li> p2, k1, p1, k2, repeat to end of round

<li> p2, k1, p1, k2, repeat to end of round

</ol> - Plaintext

What if I were to use the plaintext representation of the aforementioned list:p2, k2, p1, k1, repeat to end of round

That's actually, as I alluded before, a programmatic representation of knitting. And, were it not for that pesky "repeat to end of round", would be nearly perfect.

p2, k2, p1, k1, repeat to end of round

p2, k1, p1, k2, repeat to end of round

p2, k1, p1, k2, repeat to end of round

In fact, this is relatively close to what KnitML uses as a human-readable format, according to my reading of the spec. - S-Expressions

These little gems are the core of Lisp, and are easily transformable to and from XML if the need arises.

The core elements to them are lists and atoms. A list is multiple atoms surrounded by parentheses and separated by spaces. An atom is some text representing something.

Thus, the pattern described above becomes:(repeat 2

And any Lisp programmer reading this just started twitching. As that's not properly-formed Lisp. On the other hand, it does represent a very interesting way to mix data and instructions.

(repeat-to-end (p2 k2 p1 k1)))

(repeat 2

(repeat-to-end (p2 k1 p1 k2)))

Patterns become lists of stitches and transformative operations performed on those stitches. It's knitting as a pseudo-mathematical notation.

So, taking s-expressions as a base, what does it all mean?

Well, in that list of representations, the further along I went, the more the representation changed from being a depiction of the data to a representation. By the time we reach the plaintext version of the pattern, it is recognisable as a rudimentary program.

The s-expression version isn't even a rudimentary one; if it were fed into an interpreter that recognised the words and symbols used, it is a program to generate a knitting pattern.

Now that offers some interesting prospects, because the output of the interpreter by no means has to be fixed. For instance, I could have one interpreter that reads the pattern as a way to generate a plain text file, another interpreter that generates an SVG graphic and a third that reads the pattern as a way to generate the equivalent KnitML file.

Why does all this matter? Well, I've become interested, in the past weeks, in the idea of an editor where I type in a row of stitches and it appears on the screen as a graphical pattern. Thinking about how to represent stitches is a first step on the road to knitting pattern zen.

Swatch, knit thyself

Someday, I'm going to learn to knit tiny swatches. The first one I did for this hat was enormous, the size of a tea towel, but highlighted more than a few mistakes that I was making.

Luckily, the cable pattern is composed of repeated motifs. So, seeing these motifs work once was enough to know how they work throughout.

Unfortunately, my first sketch for the lace pattern was done somewhat foolishly. I believed that I could guess, from the pattern, what it would look like, conveniently forgetting that lace isn't just a pattern of holes: it also relies on a structure of slanted and upright stitches.

What I'm trying to say is that my first sketch was uglier than ugly. I've revised it now, and on paper, it looks nice. In practice, I don't know. So I'm doing the sensible thing this time and knitting it again.

There needs to be a pattern to the decreases anyhow, and I've no idea what that'll be. Thus, he sensible thing is 30 rows of swatch, a lifeline and then some puzzling out what decreases go where.

Why I like circular knitting

So, I'm swatching a project. A project that's 2/3 cabling and 1/3 lace. A project where there's at least one stitch pattern that's heavily used and may not even be possible.

And as is my wont, perhaps foolishly, I'm swatching it flat. 20 rows, 51 stitches. Which is fine for the lace pattern: It was meant to be flat and I can live with that. The cable pattern is much worse.

It actually looks reasonable enough charted in the round. I have a very rough sketch, written before I realised a few things. Flat, though, that's a different story.

I'm deliberately only knitting a fraction of the pattern as a swatch, and that still took me an hour and a half to draw. It's going to be fun when I draw the entire pattern, seeing as that chart is 1/125th of the pattern.

At least the pattern will be flat.

Well, after realising that I was going to be working the chart forever and ever, I re-charted the lace pattern to run 30 rows, the minimum possible to see the pattern working.

The cable pattern is only 20, but if I'm feeling ambitions, I'll extend it, just to see the whole sweep of the pattern. Unfortunately, this actually makes the swatch larger. Fortunately, only by 100 stitches.

Shadow Check Socks - Pattern

Well, they took two weeks to get together, but I'm happy to say that these socks are finally a pair. Happily, they are indeed as thick, dense and warm as I'd hoped when I first started planning for them.

Requirements

- 300m sport weight yarn

- 3.5mm double-pointed needles

- 3.5mm straight needles

- A crochet hook

Measurements

- The circumference of the ball of the foot.

- The length of the foot.

- The circumference of the ankle.

- The circumference of the middle calf.

- Your gauge in circular heel stitch.

- Your gauge in seed rib.

For the gauges, fear not. You'll be knitting a number (quite a number, in fact) of rounds of those stitches before you need to know gauge, so it's simple to measure directly on the sock itself.

Instructions

Casting On

Perform a provisional cast on of eight stitches, knitting four rows, as for the Simple Toe-Up Socks

Heel Stitch Toe

Stitches between {braces} are repeated the number of times indicated. Stitch counts are in brackets and indicate the number of stitches on both the top and the bottom.

Knit this pattern until you have enough stitches around to go snugly around the ball of the foot. End on an even-numbered round.

- Knit the entire round.

- Top: k1, kfb, k4, kfb, k1 (10)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k4, kfb, k1 - Top: k2, {s1 wyib, k1}(3 times), k2

Bottom: k2, {k1, s1 wyib}(3 times), k2 - Top: k8, kfb, k1 (11)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k8 - Top: k2, {s1 wyib, k1}(4 times), k1

Bottom: k1, {k1, s1 wyib}(4 times), k2 - Top: k1, kfb, k7, kfb, k1 (13)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k7, kfb, k1 - Top: k3, {s1 wyib, k1}(4 times), k2

Bottom: k2, {k1, s1 wyib}(4 times), k3 - Top: k11, kfb, k1 (14)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k11 - Top: k3, {s1 wyib, k1}(5 times), k1

Bottom: k1, {k1, s1 wyib}(5 times), k3 - Top: k1, kfb, k10, kfb, k1 (16)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k10, kfb, k1 - Top: k2, {s1 wyib, k1}(6 times), k2

Bottom: k2, {k1, s1 wyib}(6 times), k2 - Top: k14, kfb, k1 (17)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k14 - Top: k2, {s1 wyib, k1}(7 times), k1

Bottom: k1, {k1, s1 wyib}(7 times), k2 - Top: k1, kfb, k13, kfb, k1 (19)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k13, kfb, k1 - Top: k3, {s1 wyib, k1}(7 times), k2

Bottom: k2, {k1, s1 wyib}(7 times), k3 - Top: k17, kfb, k1 (20)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k17 - Top: k3, {s1 wyib, k1}(8 times), k1

Bottom: k1, {k1, s1 wyib}(8 times), k3 - Top: k1, kfb, k16, kfb, k1 (22)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k16, kfb, k1 - Top: k2, {s1 wyib, k1}(9 times), k2

Bottom: k2, {k1, s1 wyib}(9 times), k2 - Top: k20, kfb, k1 (23)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k20 - Top: k2, {s1 wyib, k1}(10 times), k1

Bottom: k1, {k1, s1 wyib}(10 times), k2 - Top: k1, kfb, k19, kfb, k1 (25)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k19, kfb, k1 - Top: k2, {s1 wyib, k1}(10 times), k2

Bottom: k2, {k1, s1 wyib}(10 times), k2 - Top: k23, kfb, k1 (26)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k23 - Top: k11, kfb, k1 (14)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k11 - Top: k3, {s1 wyib, k1}(5 times), k1

Bottom: k1, {k1, s1 wyib}(5 times), k3 - Top: k1, kfb, k10, kfb, k1 (16)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k10, kfb, k1 - Top: k2, {s1 wyib, k1}(6 times), k2

Bottom: k2, {k1, s1 wyib}(6 times), k2 - Top: k14, kfb, k1 (17)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k14 - Top: k2, {s1 wyib, k1}(7 times), k1

Bottom: k1, {k1, s1 wyib}(7 times), k2 - Top: k1, kfb, k13, kfb, k1 (19)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k13, kfb, k1 - Top: k3, {s1 wyib, k1}(7 times), k2

Bottom: k2, {k1, s1 wyib}(7 times), k3 - Top: k17, kfb, k1 (20)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k17 - Top: k3, {s1 wyib, k1}(8 times), k1

Bottom: k1, {k1, s1 wyib}(8 times), k3 - Top: k1, kfb, k16, kfb, k1 (22)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k16, kfb, k1 - Top: k2, {s1 wyib, k1}(9 times), k2

Bottom: k2, {k1, s1 wyib}(9 times), k2 - Top: k20, kfb, k1 (23)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k20 - Top: k2, {s1 wyib, k1}(10 times), k1

Bottom: k1, {k1, s1 wyib}(10 times), k2 - Top: k1, kfb, k19, kfb, k1 (25)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k19, kfb, k1 - Top: k2, {s1 wyib, k1}(10 times), k2

Bottom: k2, {k1, s1 wyib}(10 times), k2 - Top: k23, kfb, k1 (26)

Bottom: k1, kfb, k23

Knitting the body of the sock

First, you'll need to divide the stitches again, this time onto three needles.

Count the stitches on needles 3 and 4 and divide it by three, rounding down. This is the number of stitches that should be moved from the sole to the sides and top of the sock. For the rest of the pattern, these will be referred to as “side stitches”.

For example, I have 25 stitches on needles 3 and 4 combined:

25 / 3 = 8 1/3

8 1/3 ≈ 8

So I want to move eight stitches, or four from each side. First, transfer all the stitches from needle 4 to needle 3. Needle 3 will knit the sole of the sock, needles 1 and 2 will knit the top. Next, place a marker at the end of needle 1 and transfer half of the side stitches from needle 3 to needle 1. Place a marker at the end of needle 2 and transfer the other half of the stitches from needle 3 to needle 2. If you are moving an odd number of stitches, move the extra stitch to the needle that has fewer toe increases (needle 1 for a right sock, needle 2 for a left.)

Count the stitches on needle 3 again. If there is an odd number of stitches, perfect. If, on the other hand, it's even, transfer one more stitch. If you transferred an odd number before, place this extra stitch on the opposite needle from the odd stitch. Otherwise, place it on the needle with fewer toe increases, as above.

The pattern for the body of the sock is 6 rounds long. Stitches in {braces} are repeated, either to the end of needle 3 (for bottom stitches) or until the end of needle 2 (for top). The side stitches are knit in pattern for the top.

- Top: {Knit 1}

Bottom: {Purl 1} - Top: {k1, p1}

Bottom: p1, {k1, p1} - Top: {p1}

Bottom: p1, {yop, s1 wyib, purl 1} Here, the yarn should wrap over the slipped stitch, making one stitch crossed over the other. - Top: {k1}

Bottom: p1, {drop the yo from the previous row, si wyib, p1} Dropping the yarn over looks like it should leave a very loose stitch around the slipped stitch. However, purling the next stitch adjusts its tension, bringing it tighter once more. - Top: {p1, k1}

Bottom: p1, {s1 wyib, p1} - Top: {p1}

Bottom: p1, {s1 wyib, p1}

Knitting a gusseted heel

This is a slight adaptation of the heel described in the Simple Toe-Up Socks pattern.

Continue knitting the 6 rounds of pattern for the body until it measures 70% of the length of the foot. For me, each pattern repeat is less than a centimetre long, so you can expect this to be rather a lot of knitting. My foot is 22cm long, so I calculate that as follows:

22 cm ∗ 0.7 = 15.39 cm

Finish on round 6 of the body pattern, having just knit the bottom of the sock.

For the next while, needles 1 and 2 will not be used, so do what you will with the stitches on them, be it transferring them to a holder, placing them on a spare needle or scrap of yarn or simply leaving them on the two double-pointed needles.

The heel is knit flat and the yarn is currently placed so that the next row is the wrong side, so, to complete the shadow check pattern, knit the row, which will finish the sole with a row of purl stitches. Then, with straight needles of the same size as your double-pointed needles, knit the following 2-row pattern:

Heel Stitch

- (right side) k1, {s1, k1}

- Purl the row

This is heel stitch again. However, since there are no increases or decreases at play, it's 16 times simpler than it was at the toe.

Knit this until the heel is 95% of the length of the foot (i.e. 4-6 rows below the foot length).

Turning the heel

Next, knit row 1 of the heel stitch pattern, stopping 2 stitches before the end of the row. Turn the sock and knit row 2, stopping 2 stitches before the end of the row.

Knit row 1 again, stopping 4 stitches before the end of the row, then row 2, stopping 4 stitches before the end of the row.

Continue like this, losing two more stitches each row, until you have either 9 or 7 stitches left live and have just completed a purl row (row 2).

Next, knit row 1 again, knitting the last live stitch together with the first saved stitch and knitting the second saved stitch. Turn your work and knit row 2, purling the last live stitch together with the first saved stitch and purling the second saved stitch.

Repeat those two steps until all the stitches are live again. Congratulations. You're halfway done the heel.

Picking up from the heel flap

You should have just completed a purl row so, to get your yarn in position to knit in the round, knit across the heel one more time, this time using two double-pointed needles, one holding each half of the heel.

Begin picking up stitches along the side of the heel flap with the second double-pointed needle used to knit the heel. If you look at the selvedge, you should have a raised row of slipped stitches below a slightly-curled row of knit stitches. You'll want to pick up one stitch per row along the heel, so insert a needle in the hole beneath the two strands of the knit stitch, insert your double-pointed needle into the hole underneath it and knit one stitch.

Repeat this for every row of the heel, as well as picking up two stitches from the first stitch on the top of the sock in order to ensure that there's not a hole between the heel and the top of the sock. Note the number of stitches you picked up, place a marker at the end of the needle and knit the side stitches onto it. This keeps you from working the decreases across a gap between needles.

Knit across the top of the sock, transferring stitches onto two

double-pointed needles if needs be. With the second double-pointed

needle, pick up the same number of stitches along the heel flap as you

did on the other side, leaving a marker before the picked-up

stitches.

Finally, transfer the picked-up stitches and the side stitches to the other needle on the back of the sock. Time for the final change in needle numbering. As before, the needles are numbered in clockwise order. The two across the top of the foot are needles 2 and 3. The two making up the heel are 1 and 4.

That's it. The heel has been turned, the stitches have been picked up. All that's left is to decrease the heel gusset until the sock is the same size as it was at the ball of the foot.

Gusseting

Compared to everything you've been through so far, this bit is easy. Knit each round using the seed rib pattern. To determine where in the pattern to start count the number of stitches on needle 1. If it's even, start the pattern on round 1, if it's odd, start on round 4.

Two stitches before the marker on needle 1, stop. If you are on a knit round, K2TOG. If you are on a purl round, P2TOG. If you are on a seed round, do not decrease.

Continue knitting seed rib until you get to the marker on needle 4. If you are on a knit round, SSK. If you are on a purl round, S1, P1, PSSO. If you are on a seed round, do not decrease.

Continue knitting this pattern until you have the same number of stitches as you did for the ball of the foot.

Seed Rib

- Knit the round

- k1, p1, repeat

- Purl the round

- Knit the round

- p1, k1, repeat

- Purl the round

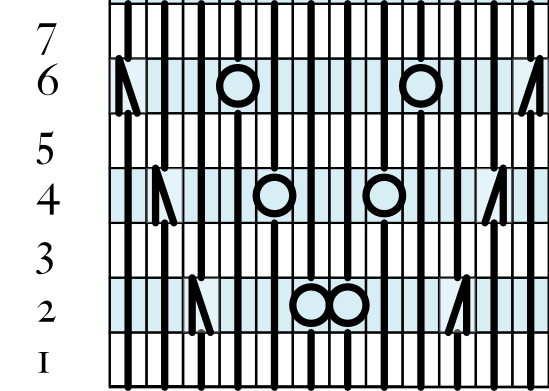

The half above the black line is the normal pattern repeat. The part below is the general pattern for the gusset decreases.

Ankle

If the ankle is to be smaller than the ball of the foot, continue knitting seed rib for three rounds. Once you have done that, work decreases as follows:

If you are on a seed round, do not decrease.

If you are on a knit round, knit the first stitch of needle 1, SSK, knit to the last three stitches on needle 4, K2TOG, K1.

If you are on a purl round, purl one stitch, S1, P1, PSSO, purl to the last three stitches on needle 4, P2TOG, P1.

Decrease in this way until you have the right number of stitches for the ankle.

Calf

Knit four repeats of the seed rib pattern. Count your stitches. If they are not divisible by 6, increase via KFBs in the knit rounds as you knit rounds 1-5 of a fifth repeat. Otherwise, knit those rounds without increase.

That done, it's time to begin ribbing. The pattern for the rib is another Barbara Walker one: embedded moss stitch ribbing, with a single amendment. It'll be worked over 6 stitches, rather than 7, to ensure that its repeat length matches that of the seed rib.

Embedded Moss Stitch Ribbing

Repeat these 6 stitches around the entire circumference of the sock.

- p2, k2, p1, k1

- p2, k2, p1, k1

- p2, k1, p1, k2

- p2, k1, p2, k2

This gives a rib that is a 2-stitch purl gutter between columns of knit stitches, with a twocolumn moss stitch pattern between them.

Knit this ribbing until the sock is as long as you want it, knit two rounds in P2, K4 ribbing, then cast off very loosely with the following pattern: P2, K4.

Shadow Check Socks - One down!

Well, I got lucky. My first knit of the ankle and calf turned out to be exactly what I wanted and my lifeline ended up being wholly unnecessary. So, with only a dozen metres or so of yarn left on my first ball, I turn to the second and begin knitting the second sock.

This becomes helpful proofreading, as for the second sock, I follow the pattern that I wrote while knitting the first. If it matches, I post the pattern as-is. If not, I edit the erroneous parts of the pattern.

While I was terribly happy to open Ravelry and mark the pattern as 50% done, I recognise that the second sock is likely to take almost as long as the first, as the slowness wasn't due to revising, but rather because the sock was simply a hell of a lot of knitting.

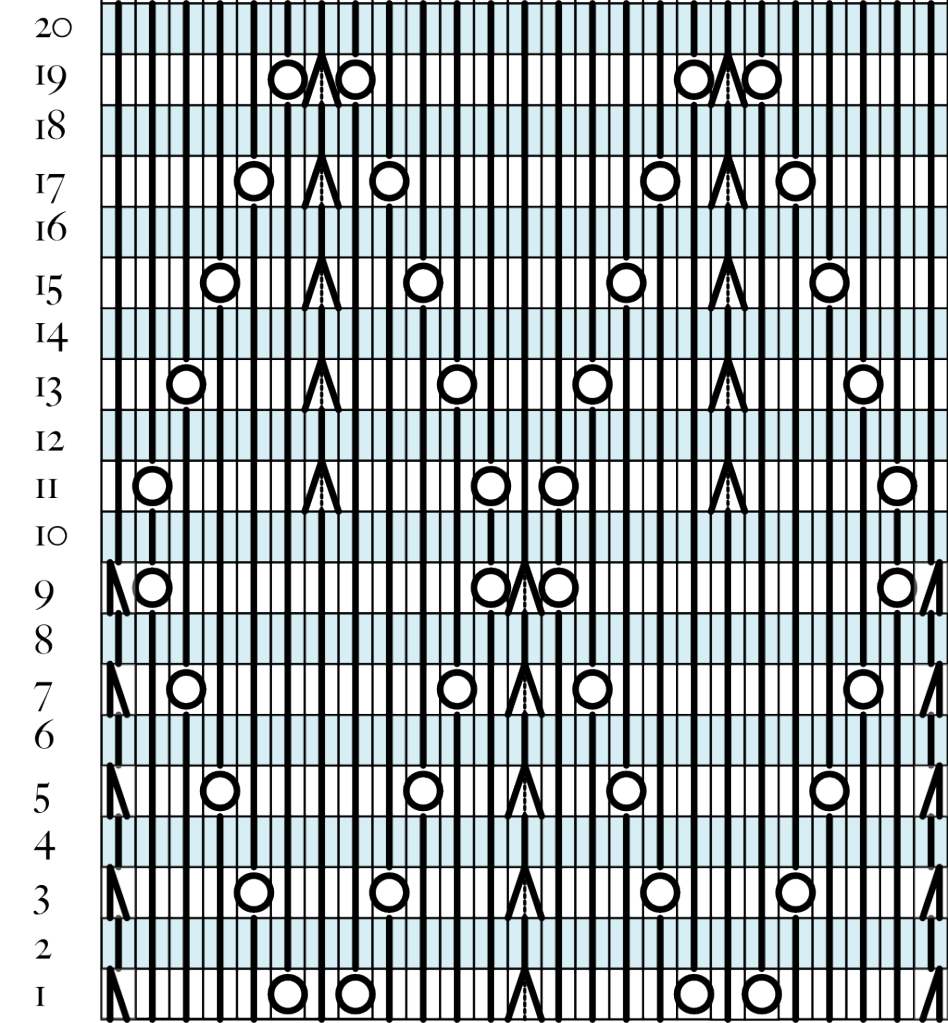

Stitch Patterns - Charts

In a little more thinking aloud, I charted the stitch patterns that I'm currently thinking about. The sensible next step would be to swatch them, but I'm going to be daft and simply lifeline my socks in another few pattern repeats and use them as the swatch.

Because I'm thinking about these patterns for socks, they're all given as circular directions, rather than flat.

Seed Rib

The half above the black line is the normal pattern repeat. The part below is the general pattern for the gusset decreases.

Stitches with a green background are repeated.

Mistake Stitch Rib

This pattern uses a multiple of 4 stitches plus 3. The stritches in green are repeated.

Embedded Moss Stitch Rib

The six stitches of this pattern are repeated throughout.

ETA (08/02/2009): Updated with better chart images.

ETA (12/02/2009): Changed the Seed Rib pattern, because the pattern of decreases in the seed rows was near-impossible to explain.

Stitch patterns

So, these socks take three, possibly four stitch patterns: heel stitch, shadow check, a stitch whose name I can't find, but will call seed rib and a pattern for the ribbing along the calf.

Shadow check and heel stitch are described in my original post about the shadow check socks. The unnamed stitch, which I shall, in future, call seed rib, is two rows garter, one row seed, two rows garter and one row seed (in the opposite pattern to the previous seed row).

My first humbling lesson was that heel stitch is incredibly difficult in the round. I've played with that some more, and in my working pattern, have managed to simplify the pattern for the toe dramatically.

My second was that shadow check draws the fabric far too tight to have any stockingette in the same row with it. That realisation led directly to my changing the seed rib from a part of the top to an all-over pattern, continuing it along the heel gusset. The decision to include it over the gusset created its own problems, though.

When decreasing for the gusset, to keep the pattern shrinking at an appropriate rate, there need to be decreases every round. The problem with that is that every third row is seed, and the decreases need to happen in pattern. Approaching the decreases, there are two possible patterns: k1, p1, k1, (marker) p1, k1 or p1, k1, p1, (marker) k1, p1. As you can see, either one of those patterns means that a 2-stitch decrease will double up a stitch. Taking the first as an example, if you k2tog, you end up with k1, k2tog, (marker) p1, k1 and if you p2tog, you have the opposite problem: k1, p2tog, (marker) p1, k1.

After several rounds of deliberation, I came up with the following pattern for decreasing the gusset in seed rows:

- Knit in pattern to two stitches before marker.

- If the last stitch was knit, k2tog. If it was purled, p2tog.

- Knit in pattern to the second marker.

- If the last stitch was knit, s1, p1, psso. If it was purled, ssk.

- Knit in pattern to the end of the round.

This ensures that the paired stitches match up nicely. Its biggest advantage, though, is that it stops what I was doing before, namely looking at the previous seed row and guessing based on that.

I still haven't decided what to do for the ribbing around the calf, though. Conceivably, I could knit the lot in seed rib, but I think I'd feel that I was ducking out. I expect and anticipate that I'll end up increasing to a multiple of five stitches and relying on that lovely standby, slip-stitch rib.

On the other hand Barbara Walker has two patterns that intrigue me. One is mistake-stitch ribbing, which looks interesting from the photos, but would have to be rather altered to work as a circular pattern. What it is is k2, p2 rib, worked on one stitch less than the needed multiple of 4 stitches, so that there is a column of knit surrounded by jagged knit and purl stitches.

The other is embedded moss stitch ribbing. That stitch pattern actually fits, interestingly, with seed rib. What it is is a pair of knit stitches enclosing two moss stitches. Converting that would be easy and looks like it'll fit with the overall texture.

Shadow Check Socks -- Time to start the heel flap

So I spent two days playing with blogger, poking at layouts and widgets, all the while glancing over at the toe of the sock with no small amount of frustration. The sock was giving me a slight case of knitter's block, not helped by my ballpark calculation that I needed 600 stitches for each centimetre of sock.

Calling them Simple Textured Socks had passed from misnomer to outright lie. The pattern may be 5 stitches and six rows, but it requires enough attentiveness that I was unable to knit it while reading (my habit for stockingette and cables).

I finally put on a TV show, buckled down and started knitting, and was quite pleased to find that the interesting nature of the textures was carrying me along. As I knitted, I was intensely curious to see how the two patterns would grow.

I'm not sure whether to call this sock pattern beautiful or ugly. "Idiosyncratic" certainly describes it. The soles are dense but soft, about three times as thick as knit stitch. Even when flattened, the fact that the sock is so very dense and thick means that it's rounded rather than sitting flat.

The uppers are about half the thickness of the soles, but have an amazing amount of stretch to them. Horizontally, they can stretch to double their width and vertically to half again their size.

As well, and thankfully, the upper part of the sock gathers tightly in the vertical direction. Since the soles take 6 rows to get the same amount of length as two rows of knit stitch, they are incredibly tight in the vertical sense. Horizontally, they have the same density as heel stitch, something that I noted with my test swatch, and am using to my advantage.

For these socks, I've been adopting my usual modus operandi, namely knitting enough of the pattern that I have a clear picture of how it should look, then typing out an actual pattern and following it, amending mistakes and missteps as I go.

To date, there have been three changes to my pattern as written:

- I initially said that some stitches along the sides of the socks should be knit in stockingette, rather than working them in pattern. I was wrong about that; it resulted in two columns of stitches that were trying to grow vertically at a rate three times that of the rest of the sock, resulting in unfortunate bulges.

- Because I was following my Simple Toe-Up Socks pattern, I indicated several rounds of decreases between the ball of the foot and the instep. As it turns out, knitting a dense and stretch material neatly removes the need for that shaping, while making the socks' fit quite close.

- I had planned to knit the gussets and the calf in simple knit stitch, but it's becoming evident to me that changing the stitch that dramatically would look bad.

At the moment, I'm vacillating between four choices:- Knit the gusset and the calf in garter stitch.

Simple, straightforward, but I worry that it'll be too plain. - Knit the gusset in stockingette but knit all stitches that are not decreased as a part of the gusset in garter. This will eventually mean that the back garter stitches and the front garter stitches meet, making the calf a continuous band of garter stitch.

This adds some decoration to the previous pattern, but I'm afraid that what happened before with combining stockingette and a tighter stitch will recur, leaving the gusset to bulge outward. - Knit the gusset and calf in the same pattern as the upper part of the sock, decreasing in pattern.

The only reason to not do this is that it continues the pattern of this sock requiring careful attentiveness. In all honesty, I should bite the bullet, suck it up and knit the pattern. - Knit the upper and back of the sock in pattern, but the gusset in stockingette.

I'm nearly certain that this idea will fail due to bulgy, unsightly gussets.

- Knit the gusset and the calf in garter stitch.

Dogwood Cabled Hat -- Pattern Amendments

I've made a little change to the instructions: In decreasing the ribbing, I said to p1, s1, psso. That's not really possible. I meant to say s1, p1, psso.

Also, I noticed that the pattern was written with my old method of typing stitches into a spreadsheet. Since then, I've set up Inkscape with a template SVG document that does a far far better job at giving me good-looking knitting patterns.

So, while updating the PDF for the dogwood cabled hat, I added in a proper graphical pattern, which looks far far prettier than the previous ASCII-art one.

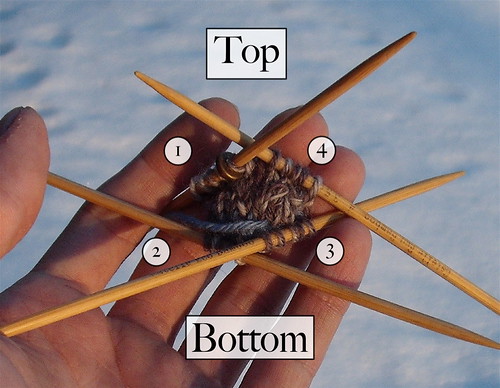

Simple Textured Socks -- Rip number 3

Well, I've ripped these things three times. One because I realised that I wanted to do the toe in heel stitch. Two because circular heel stitch while increasing is harder than I thought.

So, in the interests of not ripping a fourth time, I'm going to write out one full repeat of the heel stitch-while-increasing pattern.

It uses the needle numbering I've used elsewhere, where the two needles on top are 1 and 4, and the ones on the bottom are 2 and 3.

Heel Stitch Toe

First, knit four rows from a provisional cast on of 8 stitches and divide the 16 stitches between four needles. You'll be on needle 4, so knit that needle to get to needle 1.

- Knit the entire round.

- Needle 1: k2, kfb, k1 (5)

Needle 2: k1, kfb, k2 (5)

Needle 3: k2, kfb, k1 (5)

Needle 4: k1, kfb, k2 (5) - Needle 1: k1, s1 wyib, k3

Needle 2: k3, s1 wyib,, k1

Needle 3: s1 wyib, k1, s1 wyib, k2

Needle 4: k2, s1 wyib, k1, s1 wyib - Needle 1: k3, kfb, k1 (6)

Needle 2: k1, kfb, k3 (6)

Needle 3: k5

Needle 4: k5 - Needle 1: k1, s1 wyib, k1, s1 wyib, k2

Needle 2: k2, s1 wyib, k1, s1 wyib, k1

Needle 3: s1 wyib, k1, s1 wyib, k2

Needle 4: k2, s1 wyib, k1, s1 wyib - Needle 1: k4, kfb, k1 (7)

Needle 2: k1, kfb, k4 (7)

Needle 3: k3, kfb, k1 (6)

Needle 4: k1, kfb, k3 (6) - Needle 1: k1, s1 wyib, k1, s1 wyib, k3

Needle 2: k3, s1 wyib, k1, s1 wyib, k1

Needle 3: s1 wyib, k1, s1 wyib, k3

Needle 4: k3, s1 wyib, k1, s1 wyib - Needle 1: k5, kfb, k1 (8)

Needle 2: k1, kfb, k5 (8)

Needle 3: k6

Needle 4: k6 - Needle 1: k1, s1 wyib, k1, s1 wyib, k1, s1 wyib, k2

Needle 2: k2, s1 wyib, k1, s1 wyib, k1, s1 wyib, k1

Needle 3: s1 wyib, k1, s1 wyib, k3

Needle 4: k3, s1 wyib, k1, s1 wyib

The rules are:

- Knit on increase rows.

- Needle 1 starts on a knit stitch.

- The last two stitches on the needle are never slipped, otherwise you get holes.

- Needle 2 is needle 1 knit backwards (ends on a knit stitch).

- Needle 3 starts on a slip stitch.

- Needle 4 is needle 3 knit backwards (ends on a slip stitch).

I think, when I write this pattern out in full, that I'll write it from 4 stitches on each needle through to 60 stitches around, simply because it's not a pattern that follows easily.

ETA (7/2/2009): I've considered and toyed with this pattern more since noting it down, and the correct answer is that I'm numbering the needles wrong. Realistically, 1 and 2 should be the top of the foot, 3 and 4 the bottom.

I worked that out when trying to chart the pattern and not wanting to either write a chart with directions like "start at the middle, read right to left for needle 1, read left to right for needle 2 and 3, then right http://www.blogger.com/img/blank.gifto left for needle 4, stopping at the middle" or to write a separate pattern for each needle.

By changing how I thought of the needles, I was able to write a single chart for the top and the bottom, presented as two charts, as the bottom is the enantiomer of the top.

Deliberately, this chart goes on past what I reasonably expect as sizes, just to avoid having to try to give the extrapolation of the pattern as a process, as the algorithm for generating the toe relies somewhat on anticipating the next line.

Simple Textured Socks

This is meant as an alteration to my simple toe-up socks, but will en up with its own pattern when I'm done.

Since knitting them, I've been thinking about how to improve the pattern, and have realised that I'd like the soles thicker and softer. Barbara Walker has a stitch pattern called shadow check on page 103 of A Treasury of Knitting Patterns.

It's a lovely slip-stitch pattern, with a beautiful wrong side. The slipped stitches make it exceptionally dense, but the way it works makes it quite soft. Better still is that it can be worked over the same number of stitches as heel stitch.

However, there's a catch. As with all of her patterns, shadow check is given as a flat pattern with a right and a wrong side. Further, it doesn't easily translate to knitting in the round, at least, not easily enough that I can do it in my head, so I'm jotting down the stitch pattern, converted to circular knitting, so that I can refer to it when needed.

Shadow check (circular)

Odd number of stitches. Stitches in {braces} are repeated.

- {Purl 1}

- Purl 1, {knit 1, purl 1}

- Purl 1, {yarn over, slip 1 with yarn in back, purl 1}

- Purl 1, {drop the yarn over from the previous round, slip 1 with yarn in back, purl 1}

- Purl 1, {slip 1 with yarn in back, purl 1}

- Purl 1, {slip 1 with yarn in back, purl 1}

That pattern will make up the sole of the sock, with the right side facing out and the dense, corrugated wrong side facing in as padding. Because this will make the sole denser than simple knit stitch, I plan on having a small amount of ribbing on the top of the sock, to give the whole thing some give.

The heel of the sock will be made from standard heel stitch, which lines up exactly with shadow check and begins with a row of purl, which will serve nicely to complete the previous pattern.

Heel Stitch

Odd number of stitches. As this is worked flat, it has a right and a wrong side.

- (Wrong Side) {Purl 1}

- Knit 1, {slip 1 with yarn in back, knit 1}

Again, this is denser than simple knit stitch, but because the heel is knit flat and then gusseted, the only significant difference will be that there will be more decreases along the gusset.

Because slip-stitch patterns look really interesting when worked in multiple colours, rather than doing what I did before and knitting the toe, heel and cuff in self-striping yarn and the foot and ankle in plain, instead I'm going to use self-striping yarn for the whole thing.

Like everything, it's an experiment, but the only downside I see to this project is going to be that I can't work the sole while reading a book. Anyhow, time to cast this project on.

Two-Piece Knotwork Hat

Well, after six attempts at the brim and two test-knits plus one failed attempt at the body, this hat came together.

It began as a simple concept: I wanted to make a hat that had a single braid pattern running around the brim. From that, form ollowed design. I knew that I'd have to graft the brim into a loop and pick up stitches.

That said, when starting, I noted grafting as something that I'd have to learn and had no clue what pattern I'd attach to the body of the hat. In the end, I failed at grafting but learned a lot and ended up knitting four patterns for the body before finding one that wasn't overwhelming.

The hat itself has the shift in density that I wanted, though. Around the ears, the fabric is thick, dense and warm. Atop the head, it flates out just slightly and sits loosely on my hair, hopefully preventing it from getting tangled and staticked by the hat.

Requirements

- 150-175 metres of worsted weight yarn, preferably in two colours.

- 4mm straight needles.

- 6mm circular needles and/or double-pointed needles.

- Circular or double-pointed needles in a size smaller than 4mm.

- A tapestry or sewing needle with an eye large enough to accommodate worsted weight yarn.

Instructions

Brim

Casting on

Cast on onto 4mm straight needles using a crocheted provisional cast-on of 22 stitches. Crochet a chain, placing the yarn behind a needle after every crochet stitch and pulling it through the loop on the hook such that it wraps around the needle. Chain a few more stitches and then pull the yarn through the loop. This gives a provisional cast-on that can be easily undone later on.

Knit the following pattern (brim chart):

- (wrong side) p2, k2, p6, k2, p6, k4

- (right side) p4, k4, c2l, c2r, k4, p2, k2

- p2, k2, p4, k1, p4, k1, p4, k4

- p4, c2x2l, p1, c2x2r, p1, c2x2r, p2, k2

- p2, k2, p4, k1, p4, k1, p4, k4

- p4, k4, c2r, c2l, k4, p2, k2

- p2, k2, p6, k2, p6, k4

- p4, k2, c2x2r, p2, c2x2l, k2, p2, k2

- p2, k2, p6, k2, p6, k4

- p4, k4, c2l, c2r, k4, p2, k2

- p2, k2, p4, k1, p4, k1, p4, k4

- p4, c2x2l, p1, c2x2l, p1, c2x2r, p2, k2

- p2, k2, p4, k1, p4, k1, p4, k4

- p4, k4, c2r, c2l, k4, p2, k2

- p2, k2, p6, k2, p6, k4

- p4, k2, c2x2r, p2, c2x2l, k2, p2, k2

Note here that the only difference between rows 1-8 and rows 9-16 is that on lines 4 and 12, the centre cable slants the opposite way.

Knit this pattern until, at the end of a set of 16 rows, the flat band that you are knitting is large enough to fit around the ears. Knit row 1 again. Cut the yarn, leaving a 1 metre long tail.

Grafting

Untie the knot at the end of your crochet chain and tug on the tail of yarn to undo it. As it releases stitches, pick them up on your free needle. The stitches may be slightly twisted here, so make sure before grafting that they are in the order specified by row 1 of the pattern.

Holding up the two needles, they should be facing the same way without twisting the brim. Turn them so that the brim forms a loop with the wrong side facing out.

You'll need to graft the stitches as they lie, using knit grafting (kg) for the knit stitches and purl grafting (pg) for the purls. Or, in other words, kg 4 times, pg 6 times, kg twice, pg 6 times, kg twice, pg twice.

Body

Picking up

Hold the looped brim so that the k2, p2 rib is at the top and the p4 stockingette is at the bottom. Pick up one stitch per row around the brim. Because the body is knit on larger needles, there is no need to adjust for gauge.

Knitting the body

Count the picked up stitches. If you didn't miss any rows, you should have a multiple of 16 stitches, plus one. Find the nearest multiple of 16. If it is greater than your number of stitches, you'll be increasing. If it is less than the current number of stitches, you'll need to decrease.

Mark the beginning of the round.

Using the 6 mm needles, knit one round in p2, k2 rib. If you need to increase, knit, evenly around the round, kfb, p2. If you need to decrease, knit k2tog, k1, p2 evenly spaced around the body of the hat.

Knit the following pattern:

- p2, k2, p2, k2, p2, k2, p2, k2

- p2, k2, p2, k2, p2, k2, p2, k2

- p2, c2l, c2r, p2, c2l, c2r

- p3, c2x2l, p4, c2x2r, p1

- p3, k4, p4, k4, p1

- p3, c2x2l, p4, c2x2r, p1

- p3, k4, p4, k4, p1

- p2, c2r, c2l, p2, c2r, c2l

- p2, k2, p2, k2, p2, k2, p2, k2

Do not knit the last two stitches of this round. Instead, move your round marker back two stitches. This is the new beginning of the round. - c2l, c2r, p2, c2l, c2r, p2

- p1, c2x2r, p4, c2x2l, p3

- p1, k4, p4, k4, p3

- p1, c2x2r, p4, c2x2l, p3

- p1, k4, p4, k4, p3

These two rounds make a 4-stitch-wide twist in the columns of 4 knit stitches. - c2r, c2l, p2, c2r, c2l, p2

Knit the first two stitches of the next round and move your round marker forward two stitches. This is the new beginning of the round. - p2, k2, p2, k2, p2, k2, p2, k2

- p2, c2l, c2r, p2, c2l, c2r

- p3, c2x2l, p4, c2x2r, p1

- p3, k4, p4, k4, p1

- p3, c2x2l, p4, c2x2r, p1

Reducing

If you are knitting on circular needles, as you knit the following rounds, when the stitches become too tight, switch to double-pointed needles.

- p3, k2tog, k2, p4, k2, ssk, p1 (14 stitches per repeat)

- p2, s1, p1, psso, c2l, p2, c2r, p2tog (12 stitches/repeat)

- p2, s1, p1, psso, k2, p2, k2, p2tog (10 stitches/repeat)

- p3, c2l, c2r, p1

- s1, p1, psso, p2, c2x2r, p2tog (8 stitches/repeat)

- p3, k4, p1

- p3, c2x2r, p1

- p3, ssk, k2tog, p1 (6 stitches/repeat)

- s1, p1, psso, p1, k2tog, p1 (4 stitches/repeat)

- s1, p1, psso, p2tog (2 stitches/repeat)

Finishing

Cut the yarn and draw the tail through the stitches on your double-pointed needles. Pull it tight, knot it and weave it in.

The bottom of the brim is 4 rows of purl stitches and likely rolls in on itself. Taking a tapestry needle and yarn of the same colour as the brim, sew the selvedge to the uppermost row of purl stitches.

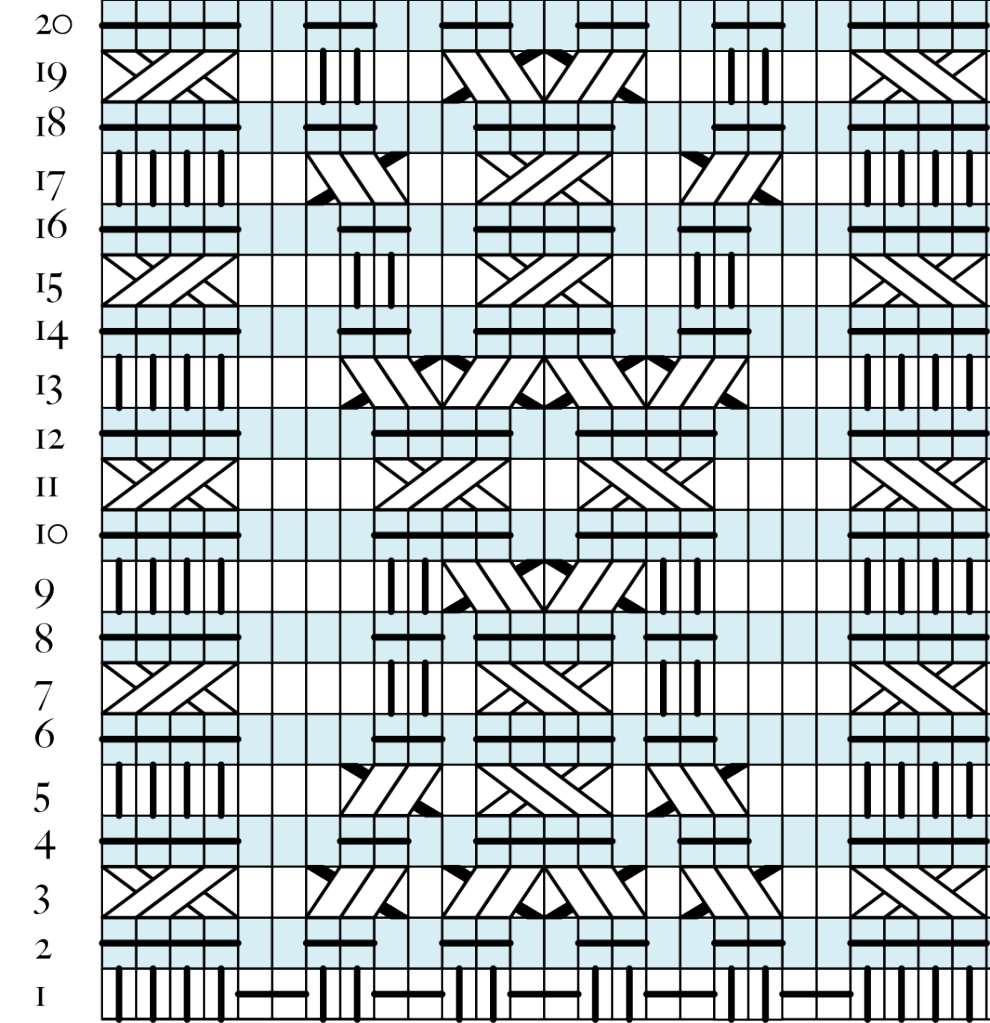

Chart

Brim

Body

Spiral-stitch hat

Here's a nice simple hat pattern that popped into my head as I was re-knitting the knotwork hat.

Cast on enough stitches (a multiple of 4) on a circular needle to go loosely around the head. Join in the round and mark your starting point.

- Knit one round of k2, p2 rib.

- Cable two left (place two stitches on a cable needle, purl one stitch, knit two stitches off of the cable needle), purl one, repeat.

At the end of the round, move your starting point forward one stitch.

When the hat fits from ears to the top of the head, begin decreasing on the purl stitches. As before, after every cable row, move your round marker forward one stitch.

Essentially,ssk the last knit stitch of every fourth rib together with the following purl stitch. Cable the next round, then ssk on the cable before the decreased one, cable again.

The chart shows four cables; the parts in purple are repeats of the pattern. Rounds 1 and 2 should be repeated until the hat is tall enough, as described above.

These decreases should spiral around to the middle, where they meet.

After you're done decreasing, pass the yarn through the remaining stitches and pull tight.

Two-Piece Knotwork Hat -- Ripping

By round 20 of the hat body, I'd made four mistakes. The biggest was that I'd cabled one of the twists left then right, but I'd also lost a stitch, realised that I wanted to alter the pattern at round 5, and didn't like how the knitted join between brim and body looked.

Solution: Rip 20, start over. I am, however, liking the feel of the second attempt more than the first, but this brings the false-start tally on this project to:

- 5 attempts at knitting a nice cable pattern for the brim.

- 2 test knits for the body pattern.

- 1 nearly-complete body ripped out.

Picking up a knit selvedge

This is a step that I first tried two months ago. I was pleasantly surprised that it was far less difficult than I was anticipating.

Preparation

You'll need the following:- Needles smaller than the ones you intend to use, of the same type (straight, circular or double-pointed.)

- Knowledge of your vertical gauge (rows/cm) in the material from which you're picking up and your horizontal gauge (stitches/cm) with the yarn and needles that you'll be using to knit new material.

It is utterly vital that your gauge be over the same measurement. Further, this will be a lot easier if the number of stitches is a whole number. 3.5 rows / cm is much harder to work with than 7 rows / 2 cm.

Picking Up

For the sake of discussion, I'll presume that your stitches on the fabric from which you're picking up run left to right. That is to say that the material has been rotated ninety degrees clockwise. If it's turned the other way, reverse all lefts and right in the directions.

Looking at the fabric, the knit stitches should make "V"s, all pointing left. Directly above those should be your selvedge stitches. Between those, above the point of the "V", there is a hole in the fabric.

Insert one needle into this hole, then the other one beneath it. There should be two strands of yarn above the needles, as you're inserting the needles between two knit stitches. Knit one stitch.

Your new stitches should pull slightly to the right, making the hole through which you knit larger and more visible. Fortunately, as you pick up the other selvedge stitches, this becomes less visible.

Repeat this process with the next stitch, inserting the needle at the hole left of the knit "V" and knitting another stitch. This will give you one picked-up stitch per row.

Equalizing Sizes

There's a problem here, as you might guess from the gauge measurements. Namely, vertical gauge is different from horizontal gauge. There's two ways to solve that problem, one easy, the other giving more control over the fabric.

To cover the easy way first, simply knit the new material on needles where your horizontal gauge is the same as the vertical gauge on the fabric from which you're picking up. That is to say, if your vertical gauge is 5 rows / 2 cm, increase the needle size to ones where you have a horizontal gauge of 5 stitches / 2 cm.

Simple enough. The drawback is that, by necessity, the new fabric will be looser than the fabric from which you were picking up. If that doesn't bother you, carry on. If it does, read on.

To figure out how the fabric has to change requires a little math.

( stitches / cm ) / ( rows / cm ) == stitches / row

So, for example, if I have a horizontal gauge of 9 stitches / 2 cm and a vertical gauge of 7 rows / 2 cm, it works out as:

( 9 stitches / 2 cm ) / ( 7 rows / 2 cm ) == 9 / 7 stitches / row

The above is why I emphasized that the measurements need to be over the same distance. So long as your measurements are the same distance, the distances cancel out. It's also why the number of stitches need to be whole numbers: to avoid having fractions like 4.5 / 3.5. This is important because later on, these numbers are used for counting stitches, and 4.5 stitches is not a valid count.

If, on the other hand, I'm going from 24 rows / 5 cm to 8 stitches / 5 cm (small needles to larger ones), I get the calculation:

( 8 stitches / 5 cm ) / ( 24 rows / 5 cm ) == 8 / 24 stitches / row

Hopefully, it's evident that this part is simply creating a fraction with horizontal gauge over vertical gauge. There's nothing more to it if your measurement is the same.

If you want, reduce the fraction, so that both halves are as small as possible. This is only necessary for mathematical correctness (or ease of counting) though, so if you don't remember how or don't want to bother, leave it as it is.

Increasing

If the numerator (top part of the fraction) is greater than the denominator (bottom part of the fraction), that indicates that you need to increase the number of stitches to meet gauge.

Subtract the denominator from the numerator. The result is how many stitches you have to gain.

If I start with 9 / 7 stitches / row:

numerator - denominator == 9 - 7 == 2

So in that example, I need to gain 2 stitches over every 7. In other words, in every 7 stitches knit, I need two increases.

Decreasing

If the numerator (top part of the fraction) is less than the denominator (bottom part of the fraction), you'll need to decrease the number of stitches to meet gauge.

Subtract the numerator from the denominator. The result is how many stitches you need to lose. The result times 2 (because a decrease takes 2 stitches and makes them into 1 is how many stitches are required to make that many simple decreases.

If I start with 8 / 24 stitches / row:

denominator - numerator == 24 - 8 == 16

16 * 2 == 32

The result tells me that I need to lose 16 stitches, meaning that I need 32 stitches to decrease, or that I need to start rethinking needle sizes.

If I start with the more reasonable 7 / 9 stitches / row:

denominator - numerator == 9 - 7 == 2

2 * 2 == 4

This time, I need to lose two stitches every 9. That is to say, I need to decrease over 4 stitches, making them into 2. Because 4 is less than 9, this change in gauge is plausible.

Actually changing the number of stitches

The easiest way is to either knit or purl a row (depending on the rest of the pattern). Work all the increases or decreases on this row, which should sit close to the original fabric.

If you're working increases, do so with an eye to the bottom of the pattern, that way a stitch knit front and back can become two knit stitches on the next row.

In either case, it looks neater if the increases and decreases are spread out across the pattern, rather than being clustered together.

Two-Piece Knotwork Hat -- Grafting and Failure

So, the brim to this hat is done; 60 cm of dense cabling. That led me to a technique that I knew I was going to have to use. Namely, grafting.

Knowing that, I turned to Google, which gave me the helpful entry on nonaKnits blog However, there was a catch: that and every tutorial I could find that made sense to me wanted to talk about stockingette. My fabric is p4, k6, p2, k6, p2, k2.

So I thought a bit. Then I forged ahead, full of hubris. And, to be blunt, I fucked up. After the fact, it occured to me that, on a project that, to date, has had six test swatches knit to get the cable patterns right, I could have spared the ten minutes to knit two pieces of stockingette-plus-ribbing to screw around with. Especially since I know better than to carry out experiments in a production environment.

That said, I learned a lot from my mistakes:

- Always, always, always swatch.

- Kitchener stitch has four actions for each stitch.

- If the yarn goes to the middle, that's a knit. If it goes to the outside, that's a purl.

- It's easiest to start on a knit stitch.

- Grafted stitches are nearly impossible to pull out.

- Always swatch, you fool.

So, that said, I now see the geometry of the two basic stitches and I'm writing it down so that next time, I don't dig myself a hole.

To start, have all stitches live and on two needles with the tips facing left as you hold them in front of you. Have a tail of yarn at least 3 times the length of the edges that you're about to graft together.

If the right side starts with a purl stitch, turn the work inside out, so that you're starting on a wrong side knit stitch.

Knit Stitch

- Pass the yarn knitwise through the first stitch on the needle nearest you. Since it is going toward the middle, it's a knit stitch.

Drop the stitch off the needle. - Pass the yarn purlwise through the next stitch on the needle nearest you.

Leave this stitch on the needle. - Pass the yarn purlwise through the first stitch on the farther needle. Since it is again going toward the middle, it's a knit stitch. Drop the stitch off the needle.

- Finally, pass the yarn knitwise through the next stitch on the farther needle.

Leave this stitch on the needle.

Purl Stitch

Unsurprisingly, the purl is simply the inverse of the knit.- Pass the yarn purlwise through the first stitch on the needle nearest you. Since it is going away from the middle, it's a purl stitch.

Drop the stitch off the needle. - Pass the yarn knitwise through the next stitch on the needle nearest you.

Leave this stitch on the needle. - Pass the yarn knitwise through the first stitch on the farther needle. Since it is again going toward the outside, it's a knit stitch. Drop the stitch off the needle.

- Finally, pass the yarn purlwise through the next stitch on the farther needle.

Leave this stitch on the needle.

In the case of this hat, I'm going to suck it up, live with my mistakes and carry on. Fortunately, the next step in this project is far less arduous: picking up one stitch per row of ribbing from a knit selvedge.

Two-piece Knotwork Hat -- Brim 1

I'm knitting, flat, the brim of a hat which will eventually be joined together and picked up. This is the chart that I'm following, a paired three-strand braid. The left side will be picked up and be knitted with a further knotwork pattern. The right side will be folded over and sewn together, to make a rolled border.

I'm knitting, flat, the brim of a hat which will eventually be joined together and picked up. This is the chart that I'm following, a paired three-strand braid. The left side will be picked up and be knitted with a further knotwork pattern. The right side will be folded over and sewn together, to make a rolled border.

Dogwood Cabled Hat

I've just finished knitting this hat, with a cable pattern of stylised trees. The trees themselves are based on a binary tree structure, but have twists and knots around themselves and around other branches. The way the branches converge into a cluster reminded me of groves of dogwood, hence the name.

The trunk expands (via a pair of decreases and increases), then splits into two branches. These branches twine once around themselves then split again, the four split branches twining before dividing yet again into a meshwork of twisting branches that stretch to the top of the hat.